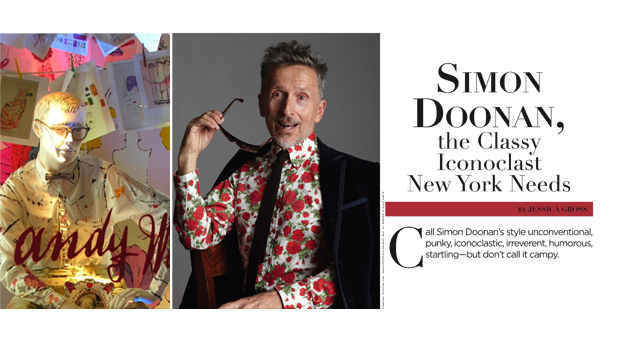

Simon Doonan, the Classy Iconoclast New York Needs

By Jessica Gross

Call Simon Doonan's style unconventional, punky, iconoclastic, irreverent, humorous, startling - but don't call it campy.

I love camp, but try to avoid anything that is ‘campy,’” says Doonan. “It might sound like splitting hairs, but there is a huge difference between real camp—a la Susan Sontag—and ‘campy,’ which tends to mean predictably tacky. High camp—like Liberace, Carmen Miranda and La Lupe and Oscar Wilde—is the lie that tells the truth. It’s a beautiful thing.”

Doonan, who currently serves as Barneys’ creative ambassador-at-large and is married to the designer Jonathan Adler, spent years creating famously wacky and wonderful window displays for the store. A tour through the sample of windows pictured on Doonan’s website, from 1998’s “Christmas Cabaret” to 2006’s “Warholiday” to 2010’s “Food Fight,” gives a sense of the boisterous extravagance that marks his style. One of the very simplest displays, “Mr. Potato Head,” features three clothed mannequins whose heads are replaced with a shoe apiece; across the floor, lined up in neat rows, are—you guessed it—standing, smiling Mr. Potato Head dolls. And then, there’s a more startling display: “Dominatrix Margaret Thatcher.”

Doonan’s relentless explosion of norms and boundaries has much to do with his personal history. In The Asylum, his most recent book, Doonan explains that he comes from “a long line of lunatics—my genes are liberally accessorized with manic depression and schizophrenia.” His grandmother was treated with a lobotomy, and he was terrified of following her path, or in that of his suicidal Uncle Dave…or his Weltschmerzafflicted grandfather…or his Uncle Ken, treated with electroshock therapy. In spite of the seriousness of his subject, Doonan addresses this topic with characteristic humor—“These nagging dreads have produced in me an abiding interest in psychiatric disorders, which itself borders on psychiatric disorder,” he writes in the book—but also notes that it partially motivated his pursuit of freedom via geography and career. “It added to my feeling that I needed to escape,” he said.

The other part of this feeling stems from Doonan’s childhood in Reading, England, which he describes in The Asylum as a “crap town.” “If you become glamour-struck, but you are stuck in the boonies, then you become obsessed with escaping,” he says. “This makes you determined and passionate. The world of fashion shimmered on the horizon and I was determined to reach out and touch it.” In the book, Doonan points out that this origin story isn’t unique among fashionistas, many of whom seek out “the accepting arms of mother fashion” as a contrast to their dislocating, gritty pasts.

“There is a kind of reverse chic about crap towns, which is hard to understand unless you were born in one,” Doonan writes. “We escapees have enormous affection for our birthplaces. Whether we hail from Fresno or Scranton, Ickenham or Twickenham, we celebrate our gritty roots while simultaneously rejoicing in the fact that we escaped.” And by “we,” Doonan means a tremendous list of fashionable creatives, including Cristobal Balenciaga, Michael Kors, Mario Testino, Jean Paul Gaultier, and Kate Moss—people who “have that creative self-assurance which comes from being born on the naff side of the tracks but knowing that your innate sense of style and your outlier creativity were sufficiently major to propel you out of obscurity.”

Doonan’s own propulsion came about after college, when he’d returned to Reading to take a job at John Lewis, a local branch of the department store, where he kept clocks feather-dusted and fully wound. At the same time, he lived a secret double life in the underground gay scene. When Doonan was transferred to John Lewis’s luggage department, he met a coworker’s friend, Eric, who worked as a dress designer in London. Eric’s story fueled Doonan’s own fantasy of a life beyond, offering “a potential escape route,” he writes.

Doonan insists that his incredible career isn’t the result of a long-term goal. “Lots of great opportunities fell in my lap and I grabbed them,” he says. But his contact with Eric did spawn that first specific fantasy—one might even say goal—of a glamorous life in fashion. “I had stared at the distant glittering mirage of fashion, smoldering seductively on the horizon, for most of my short life,” Doonan writes. “I was yearning to reach out and touch it. Eric the missy separates designer had brought me one step closer.”

Doonan began to dress windows for John Lewis, then moved to London to do so for Aquascutum, followed by Nutters of Savile Row. There, he mounted a display of taxidermy rats wearing diamond chokers. (Remember: iconoclastic, irreverent, humorous, and startling. High camp.) The Los Angeles department store Maxfield took notice, and hired 25-year-old Doonan to dress windows there, where he stayed for eight years. In 1985, Doonan worked under Diana Vreeland for a few months designing the displays for the Metropolitan Museum Costume Institute’s Costumes of Royal India exhibit, through which he met the owner of Barneys New York, who hired him. He’s worked there ever since.

At Barneys, Doonan's unmatched style has flourished, and—especially during the holidays—provides a welcome counterpoint to traditional displays. In fact, Doonan’s work, despite its subversion, became so well regarded that in 2009, Desiree Rogers asked him to do the White House’s holiday display. “Decorating the White House for the first Obama Christmas was the high point of my display career and it was a huge honor,” Doonan says. As the “First Elf,” as Doonan puts it, he decided to reuse many old ornaments from the White House warehouse on the Christmas tree. (There was a bit of a kerfuffle from the press about certain iconoclastic decorations, including ornaments featuring drag queen Hedda Lettuce and Mao Tse-Tung.) Now, as creative ambassador at Barneys, Doonan hosts events and communicates with the press, and is no longer directly involved in window decoration.

Though Doonan’s look is obviously cultivated, and his success is born of tremendous skill and hard work, it does seem to have emerged from a continued commitment to the job at hand rather than the pursuit of a particular lofty endpoint. Take his writing career, which came about when his publisher asked him to write the introduction to Confessions of a Window Dresser, a photo book of Doonan’s creations. He was 46 years old and had never written before, but the introduction was so delightful that his publisher suggested he keep going. He’s now written thousands of columns, for both the New York Observer and Slate, and a half dozen books. “My writing career was an accident,” Doonan admits. “I always tell young kids to chill out about their career. Let it unfold. As Tyra says, ‘Don’t get it twisted.’”

Limitations can breed creativity, and Doonan’s career is a testament to that fact. Not only did he relish working up window designs at times when Barneys was struggling financially—“I do well with a small budget. I love papier mache. Who doesn’t?” he says—but his outlandish style is a reaction to the poverty, mental illness, and geographical constriction of his past. Having jumped off that springboard, lurching from limits to the unknown, why not go the full distance? Fashion offered Doonan a lifeline; in turn, he transformed fashion.

“Breaking rules and being unconventional is the key to creativity,” he said. “It also makes me happy. I started doing messy windows simply because I got tired of looking at prissy tidy ones.”